Archive

Island Voices through Indian Languages

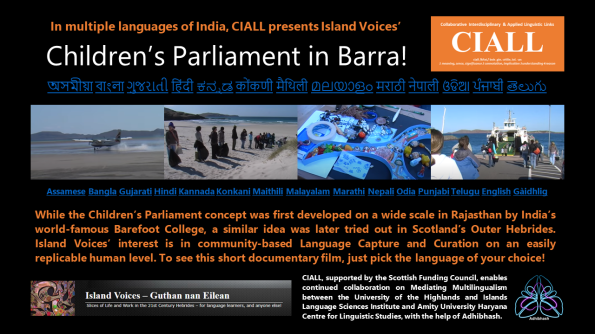

Select any language in this landscape poster, or use the phone-friendly portrait layout.

Select any language in this landscape poster, or use the phone-friendly portrait layout.

The Children’s Parliament concept was first developed to scale in Rajasthan by India’s world-famous Barefoot College. UNESCO documented some of this fascinating history-in-the-making in video form. A similar idea was later tried out in the Outer Hebrides by the Scottish Children’s Parliament organisation, which continues to work across the country to this day.

Around the time of the Children’s Parliament in Uist and Barra project, Island Voices was already developing its interest in community-based Language Capture and Curation on a shareable human scale, so recording this meeting of the Children’s Parliament in Barra (as well as the follow-up in Benbecula) was a natural step to take, with versions in both Gaelic and English included under the Series 2 Generations theme.

Following years of grounded Hebridean growth and developing partnerships, Island Voices came to Indian linguistic attention through the Mediating Multilingualism collaboration between the UHI Language Sciences Institute and AUH Centre for Linguistic Studies, serviced initially through the Soillse network and continued now by CIALL. This work has been generously supported by the Scottish Funding Council, and publicised through their EDI blog.

This brings us up to the present day, and this testing at scale of the notion that short documentary films with a focus on localised linguistic communities can be both easily and usefully re-purposed in other languages in which similar issues around contact, use, and sustainability may also be pertinent. We’ve been doing it off and on in ones and twos for a while through our Other Tongues theme. Moving in one go from two versions of one film to fifteen is a significant step-change!

The image at the top of this post, available in landscape or portrait layout, supplies live links to the film in each of the languages listed, as well as to relevant websites of the partners mentioned. Alternatively, you can just click on any of the language names in the top row of the tables below to get straight through to the YouTube version of your choice.

| অসমীয়া | বাংলা | ગુજરાતી | हिंदी | ಕನ್ನಡ |

| Assamese | Bangla | Gujarati | Hindi | Kannada |

| कोंकणी | मैथिली | മലയാളം | मराठी | नेपाली |

| Konkani | Maithili | Malayalam | Marathi | Nepali |

| ଓଡିଆ | ਪੰਜਾਬੀ | తెలుగు | English | Gàidhlig |

| Odia | Punjabi | Telugu | English | Gaelic |

(The English name of the language in the second row is a live link you can click to get to the Clilstore unit, in which the online transcript – with the video embedded – enables one-click access to an online dictionary for any words you don’t know.)

We are particularly indebted to Adhibhash for their vital work in recruiting and co-ordinating a wonderful team of translators and narrators who worked at pace to deliver these great new recordings!

The primary aim for Mediating Multilingualism was to deliver innovative and collaborative work of genuine value for partners outside Scotland. We have continued in that spirit, while recognising also the mutual benefit derived. It will not have escaped local notice that several of the languages listed above, notably Punjabi, as well as Bangla and Gujarati, are widely spoken (and taught to some degree) in “diaspora” communities here, while Hindi (or Urdu) may still serve as a link between speakers of different South Asian languages in the UK.

And as we, in Scotland, continue to struggle at community level to develop an equitable working relationship between English and Gaelic which would enable both to be fruitfully used, we might do well to remind ourselves that other countries appear to handle regional linguistic variation of far greater complexity. India has 22 scheduled languages written in to its constitution, including all those on our list above, mostly associated with different regions or states. It’s a longstanding example of differential recognition of, and official support for, local languages across multiple regions within one overall polity, as well as some which cross international boundaries. If there’s truly a mind for it, is it really beyond Scotland’s wit to meaningfully recognise “Areas of Linguistic Significance” for Gaelic within its own borders?

Returning to the Indian context and the Barefoot College, they had their own 50th anniversary celebrations in 2022. If you follow this video news report, at 11.36 you can find an interesting alternative take on literacy and education from founder Bunker Roy, in terms that again chime nicely with the Island Voices focus on the Primacy of Speech:

“Illiteracy is not a barrier for anyone to become a barefoot engineer, communicator, designer, architect… We have learnt that there’s a big difference between literacy and education. Literacy is what you learn to read and write. Education is what you get from your family environment, and your community. So our stress at the Barefoot College has always been on education. Literacy may be there, but it’s incidental for me. What is more important is the human being behind – the person who is working with us. Has he or she got the compassion, patience, tolerance, simplicity? All these are Gandhian values, which we think should set an example for anyone working in the college…”

This may be considered a simple statement of fundamental principles. But it is also perhaps another reason, alongside the recently cited example of Duncan Ban MacIntyre, to recognise anew the importance of natural speech in a community setting as the crucial ingredient in any attempt at creating a definitive recipe for promoting genuinely communicative use of any language, no matter what its circumstances. That said, none of the newly added languages here could be considered at risk of disuse in the way Gaelic is, except perhaps in diaspora contexts. But if the Island Voices home-grown and “haund-knitted” (may we call it “barefoot”?) capture and curation model works for these, could it not also be applied with other indigenous and endangered languages, whether in India, Scotland, or elsewhere?

Recent Posts

- Gaelic in Shetland

- O Parlamento de Crianças

- CEUT Reflections 4

- Alasdair Tuxy – Sgìre a’ Bhac

- Taighean-tughaidh playlist

- Jamiekan ina Wielz

- Kenny Murdo ‘s Christine Dhòmhnaill Ghoidy

- Island Voices through Indian Languages

- Rena MacIver (Bean a’ Pheadaran)

- The Composer, Duncan Ban MacIntyre

- “Baile m’ àraich” – Catrìona Dhuirl

- Donnie Macaulay – Sgìre a’ Bhac

- Back School Memories

- Scottish Studies goes fully online

- Talk on Minority Language Protection

- Retro Retrieval

- Island Voices “make sense”

- CEUT Reflections 3

- CEUT Reflections 2

- CEUT Reflections 1

Archives

Pages

Blogroll

- Am Baile

- Am Pàipear

- An Radio

- Bòrd na Gàidhlig

- British Council ESOL Nexus

- Comhairle nan Eilean Siar

- Cothrom Ltd

- HIPP

- Island Voices Audios: Ipadio Channel

- Island Voices Videos: YouTube Channel

- Leonardo

- NATECLA Scotland

- Sabhal Mòr Ostaig

- Scottish Government: Lifelong Learning

- Soillse

- TOOLS & POOLS Projects

- Ulpan – Gaelic for adults

- University of the Highlands and Islands