Archive

Gaelic in Shetland

Select any video clip in this landscape format, or use the phone-friendly portrait layout.

Select any video clip in this landscape format, or use the phone-friendly portrait layout.

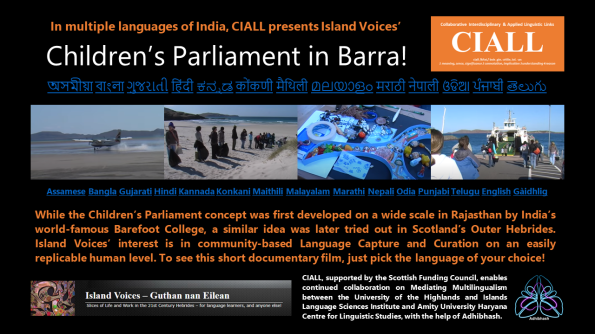

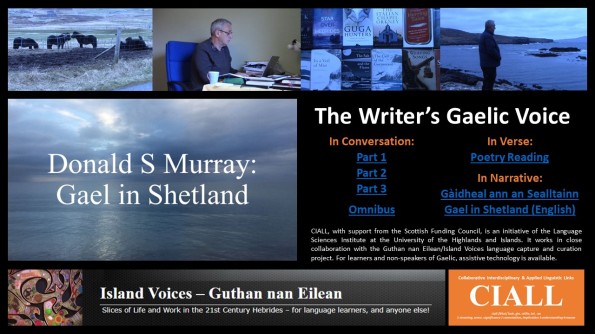

Lewis-man Donald S Murray is a Shetland resident. As an established writer, mostly in English, how does he keep his Gaelic going while living away from the Ness community where he acquired it?

Following on from our recent “Jamaican in Wales” feature, that’s a key question underlying this second small collection of videos in our Island Voices extension series looking at language use in an “exile” context. Again, we have added poetic recitation to the standard documentary plus interviews format in our Language Capture and Curation model, with the narrative documentary also being reduplicated in English. All films in the collection can be accessed through the above poster in either landscape or phone-friendly portrait layout.

As Donald freely acknowledges, he mostly uses his Gaelic for talking rather than writing, and we’ve duly given greater weight in this package to his conversational voice, though we’re pleased to also platform some of his less well-known Gaelic poetry. While he obviously has many Gaelic speakers in his ever-widening readership, there will also be many non-speakers of Gaelic who, up until now, will only know his “voice” through the written English page. Here he speaks openly and frankly in what he accounts his native language, establishing direct unfiltered contact with his home community in Lewis. At the same time, YouTube subtitling allows others to read his words as he speaks, with the on-off choice of auto-translation into a wide range of other languages, English among them. (Click the Settings Wheel to view the full range and select your own preference.)

The conversation component has additionally been split into three parts, for the benefit of learners or non-speakers of Gaelic, each equipped with optional closed caption subtitles. The “omnibus” edition is intended for those with no need for such assistance.

In Part 1 Donald talks about his family background and upbringing, first in East Kilbride and then in Ness, Isle of Lewis. He also talks about community and school influences and how they affected his acquisition of Gaelic. A spell of work and then university studies followed on the mainland, before he returned to the Western Isles to teach, first in Lewis, and then Benbecula. He also refers to challenges he had to overcome during these stages of his life.

In Part 2 Donald talks about life as a Gaelic speaker in Shetland, noting how he maintains his speaking skills through long-distance conversations and frequent radio interviews. He points out the relative infrequency of his writing in the language as a common feature amongst fluent Gaelic speakers who normally practise their literacy through English, so his writing about his home community is often a process of translation from Gaelic in his head to English on the page. He regrets the lack of theatre-based literary work in the Western Isles, and highlights the value of the short story format in an island community setting. One advantage of living away from Lewis is the greater freedom he now feels to express critical opinion freely.

In Part 3 Donald talks in some detail about the difficulties he encountered in first writing his novel, As the Women Lay Dreaming, and then in talking about it afterwards, often in relation to dealing with varying experiences of trauma at personal as well as community levels. The theme returns in a very different community context in The Salt and the Flame, exploring urban American tensions through Gaelic emigrant eyes. He is thankful for his father’s encouragement of his wide reading interests as a young boy in Ness, which are reflected in the book alongside the wider research he conducted as part of the writing process.

O Parlamento de Crianças

Um pequeno documentário em Português sobre um encontro do Parlamento de Crianças de Uist e da Barra

Um pequeno documentário em Português sobre um encontro do Parlamento de Crianças de Uist e da Barra

At Island Voices we welcome participation and contributions from speakers, learners, and researchers of any age and stage in multiple languages from all over the globe!

Marina Yazbek Dias Peres is a student in the Research Program at Princeton High School, New Jersey, in the USA. In this program, each student learns to research, and conducts their own project over the course of three years. Marina’s research project is focused on “uncovering the motivation behind the preservation of dying/endangered languages, and analyzing the causation behind the lack of their use”.

Marina is bilingual in English and Portuguese, and is also studying French and Mandarin in school. During discussion of her research topic with Gordon Wells she kindly offered to add Portuguese to the Island Voices list of “Other Tongues“, choosing the Children’s Parliament in Benbecula film in Series 2 Generations. We were happy to accept! Perhaps her example will inspire others like her to take an interest and think about participating too?

A wordlinked transcript with the video embedded is available here: https://multidict.net/cs/11930

CEUT Reflections 4

Here’s the fourth of our series of blogposts by Mary Morrison, with help from Archie Campbell and Zsuzsanna Ihar, in which she reflects on the Aire Air Sunnd project led by Comann Eachdraidh Uibhist a Tuath. As with her previous posts, comments are welcome!

Mary writes:

Cafaidh Gàidhlig agus Feasgar Dimàirt.

‘Even the sheep and cows seemed to know who we were.’

During February and March the wellbeing and Gaelic groups have spent an interesting time sharing our thoughts about the place of North Uist, based on the key findings of the CEUT 2023 Community Survey. We have tried to explore further the unspoken, deeper meanings lying beneath our concerns, in order to provide more pressing evidence to convince potential funders of the urgency of our bids for the refurbishment of Sgoil Chàirinis, as a Gaelic, heritage and wellbeing community centre.

The common concern underlying these activities is our attempt to define CEUT’s role in so far as it may contribute to the local communities’ sense of wholeness, robustness and cheerfulness. The project wants to encourage some form of cultural shift, using the aspects of our place that are our greatest assets to fortify the island’s biological, environmental and human wellbeing. The wisdom inherent in vernacular voices and local practices may be best suited to reach the centres of power and exert some influence?

The ideas developed during Feasgar Dimàirt will also be incorporated into a community mural, (or separate panels of such a wall hanging) to celebrate the unique heritage and resilient Gaelic culture of North Uist – a collaborative visual legacy for the project, and a way of combining a wide range of the communities’ artistic and storytelling talents. We are grateful to our partners here, Caraidean Uibhist and Sgoil Uibhist A Tuath for collaborating so willingly in this placemaking effort.

To begin the process of mural shaping we discussed what made us most happy about living on North Uist. The listening was intent, the group itself seemed at home, offering respect, calmness and space to put complex ideas and feelings into words, at our own pace, often qualifying and refining these.

Our recurring ideas:

- the magic or spell of the place, the land and its unique, unchanged qualities

‘Clarity of the light’, ‘changing colours of the water’, ‘layers of colours of the sand the seaweed and the sea as it stretches to infinity’, ‘poetry of creation’, ‘the sound of the sea’, ‘roaring like traffic’, ‘mindfulness’, ‘losing yourself’, ‘birdlife”, ‘walking for ever without a destination’, ‘the capacity of the environment to change so suddenly’, ‘peace and beauty’, ‘a constant surprise’.

- identity, family and ancestors – especially for our indigenous dwellers

Gaelic method of reciting of the male members of a family tree, sloinneadh, all the precious ‘connections to the local community’, heritage of knitting, peats, creel and rope making, weaving, families widening out but often returning, ‘recognising our closeness to other cultures‘, ‘confidence in new life’, growth – babies of all species- keeping the ceilidh culture and the songs going, the ‘friendliness’ of the community.

Gaelic method of reciting of the male members of a family tree, sloinneadh, all the precious ‘connections to the local community’, heritage of knitting, peats, creel and rope making, weaving, families widening out but often returning, ‘recognising our closeness to other cultures‘, ‘confidence in new life’, growth – babies of all species- keeping the ceilidh culture and the songs going, the ‘friendliness’ of the community.

- placemaking, local names, wells and the need to map, signpost and mark these

‘Views that have remained unchanged from what our ancestors saw’, noticing the changes in coastline, species, disappearance of Gaelic, wells, standing stones and their stories, some urgency to preserve. ‘Getting more sentimental as I grow older’. Mention here of milestones, waymarks trails, mapping the area for future generations and visitors, with the stories attached to them.

- and for settlers or returners, the profound sense of suddenly belonging, feeling at home and enriched by the place

‘Last night the tide was very high, I went out and stood, just watching it.

I suddenly felt so glad to be living.’

‘Glad to be here’

‘Coming from a dry, hot and dusty area, the silence, nothing, the sound of the sea was astonishing.

‘Even the sheep and cows seemed to know who we were’

The Cafaidh Gàidhlig sessions were also held in Sgoil Chàirinis over February and March. Smaller numbers here made these more intimate occasions and provided Gaelic speakers with an opportunity to speak freely in an informal setting. Games and learning activities, including the new Gaelic version of Scrabble and a beginners’ Gaelic lesson were available each morning.

The Cafaidh Gàidhlig sessions were also held in Sgoil Chàirinis over February and March. Smaller numbers here made these more intimate occasions and provided Gaelic speakers with an opportunity to speak freely in an informal setting. Games and learning activities, including the new Gaelic version of Scrabble and a beginners’ Gaelic lesson were available each morning.

Gaelic speakers were able to engage fully in profound conversations without having to give way to English. What was noticeable, to a learner was the ‘comfort’ of the speakers, the remarkable concentration on listening to each other, the lack of interruption, the implicit natural respect in turn taking, the quality of engagement, agreement and reinforcement for each speaker, the rapidity of the flow of cadence and expression, together with the ease and frequent hilarity of the discussion. To a learner, it felt like a privilege to be included so fully within the ‘cosmos’ of the language as it is spoken naturally, something that lessons rarely capture.

Areas discussed included:

- people’s experiences of attending school away from Uist and living in school hostels and all that that entailed in terms of displacement and Gaelic use

- broader discussion of the use of the Gaelic language in the Uist community

- the urgency of what we can do to ensure that Gàidhlig has a future as a viable community language

- recognition that we need to make people aware that the language is here, and to use it in as many contexts as possible (for example, a young woman who works in a local supermarket told us that it is quite normal for her to use Gaelic in her encounters with customers, but less so in other settings)

- we recognise the use of Gaelic depends heavily on the context. Discussion of the importance of parents of those in Gaelic-medium education using Gaelic in the home and socially

- recent research has shown that Gaelic has been losing its ‘domains’ of use in the public sphere, but also in social life, particularly amongst the young.

- use of digital, Gaelic and bilingual mapping for waymarking walks to local heritage sites

There followed a discussion about activities which would promote Gaelic and provide a greater presence for the language in the community.

- one man present had provided crofting life experiences in the past

- CEUT has organised summer walks to sites of interest over the past few years. The walks have been led by Gaelic speakers and delivered primarily in Gaelic. People have commented on how much they enjoyed listening to the information being presented in Gaelic, even if they didn’t understand all, or indeed, any of it. An English ‘crib sheet’ was always available .

- the valuable interviewing and recording work which has taken place over the years, preserving people’s language, knowledge and experience. This work is very much ongoing and can be found on Guthan nan Eilean. It can also also be enriching for both interviewer and interviewee

- The observation was also made that the register of Gaelic language used depends heavily on context and setting

A discussion followed as to what may be done to ensure that Gaelic has a viable future as a living community language in the face of many challenges. The most pressing being the lack of Gaelic use among the young, for whom English tends to be the default language, even for those attending Gaelic-medium education.

Members of both groups expressed a wish for the two activities to continue and we are hoping these will become monthly CEUT events, keeping up the momentum, closeness and energy the pilot events have inspired. We have recorded the speakers who have led the discussions so far and still have more to record, especially the evening talk on Coastal Erosion with Stuart Angus in the final week in July.

As Michael Newton states in ‘Warriors of the Word’:

‘As the Gaelic sense of place is one in which communal history is embedded in the placenames attached to landscape features, it depends to a great degree upon understanding the language in which the placenames were coined’.

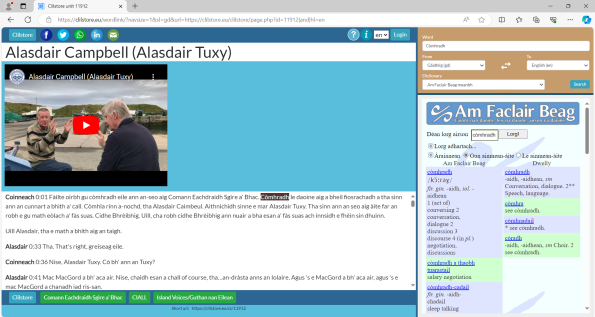

Alasdair Tuxy – Sgìre a’ Bhac

“Fàilte oirbh gu còmhradh eile ann an-seo aig Comann Eachdraidh Sgìre a’ Bhac …”

Alasdair Campbell (Alasdair Tuxy) is interviewed by Coinneach MacÌomhair at Breivig Pier.

And with CIALL assistance, another wordlinked transcript has now been created on the Clilstore platform:

Taighean-tughaidh playlist

Island Voices has created a new playlist on the YouTube video channel for the collection of recordings made about Uist’s taighean-tughaidh – thatched houses. First contributions have come from Tommy MacDonald, telling some of the history from the site of Tobhta Mhic Eachainn and its connection to the “French Macdonalds”, and then quizzing his wife Betty on her memories of being raised in a taigh-tughaidh.

These recordings have been broken up into bite-sized manageable chunks.

In the first two from Tobhta Mhic Eachainn, Tommy presents some stories about Neil MacEachan and his son Alexandre – the “French Macdonalds” – from the remains of Neil’s original house, which was later to be visited by the Duke of Tarentum in an act of filial homecoming following the Napoleonic wars. The video descriptions include links to Clilstore online transcripts for both of these clips, which are also optionally subtitled.

The conversation with Betty comes in four parts. In the first section Betty recalls who built her house (her grandfather), and aspects of her childhood life on the croft, including the herding and milking of the cattle, as well as some of the thatching process as she remembers it.

In the second part Tommy and Betty go on to discuss some of the stiff challenges that would be entailed in keeping a traditional thatched house on a par with modern standards. Talking about the cèilidh culture of earlier times, Tommy recalls how stories would be shared between family members and visitors – some of which remain unexplained to this day.

In the third section Betty and Tommy’s attention turns towards food and drink, and the important place of staples such as eggs and milk – and sometimes rabbit. Services such as electricity and water were a relatively recent introduction. They recall some of the other thatched houses in the area, with a handful having been done up to meet modern standards.

Finally, in the fourth part, Tommy and Betty share memories of more recent times, when a thatched house was converted into a hostel for tourists, under Betty’s mother’s care. In the early days visitors would often stay for weeks, helping out on the croft, and they are fondly remembered. To end, more stories are shared of amusing and perplexing incidents.

Again, Clilstore links are available in the video descriptions, with auto-translatable subtitles an additional option for learners or non-speakers of Gaelic.

The seventh video in the playlist is a longer “omnibus” edition of the Tommy and Betty conversation, which is presented without transcript or subtitles.

With Tommy planning further recordings in the community we can expect more additions to this work in progress in coming weeks, with ongoing CIALL support and in collaboration with the UHI archaeologists based at Cnoc Soilleir.

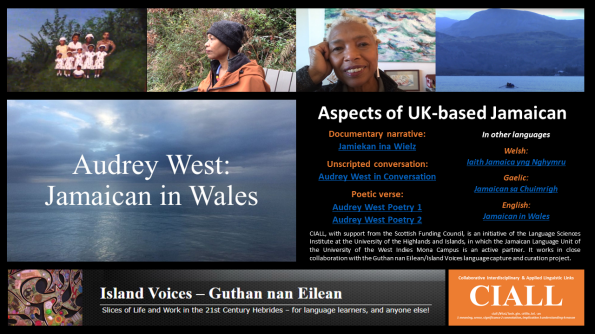

Jamiekan ina Wielz

Select any video clip named in this landscape poster, or use the phone-friendly portrait layout.

Select any video clip named in this landscape poster, or use the phone-friendly portrait layout.

Island Voices is extending its “language capture and curation” model, with CIALL support, to new contexts, new genres, and new languages, including the recording of aspects of UK-based Jamaican language use. Gaelic enthusiasts can rest assured this development does not represent a move away from our key linguistic interest in the Outer Hebrides! Far from it, as we engage with other language communities near and far, new opportunities are created for fresh spoken material in video format in Gaelic (and English – and other languages).

We recently filmed Jamaica-born, but London-raised, artist and poet Audrey West at her home in Wales. (Keen followers may well recognise Audrey from her previous contribution to our “Talking Points with Norman Maclean” debates.) We have now created Island Voices-style short video clips in the familiar “documentary” and “interview” formats, while adding a third category of “recitation”, newly included to capture Audrey’s poetry. These films are all listed in the poster above. You can click for either landscape or portrait versions to access live links to any and all of the videos created,

We’re also indebted to Dr Joseph Farquharson from the University of the West Indies Jamaican Language Unit (another Talking Points contributor!), for overseeing the creation of the documentary script in the institutionally approved Cassidy-JLU orthography. Joseph and the JLU team have been extremely busy recently, also providing expert advice to Kingsley Ben-Adir and other cast and production team members for the “Bob Marley: One Love” biopic. As one commenter(!) put it, this YouTube discussion provides “really interesting insights into how skilled linguistic, particularly phonetic, analysis and description can percolate beyond academia and deliver practical applied impact. Bravo JLU!”

This system has enabled regularised subtitling of the clip on sound linguistic principles. Ironically, as YouTube/Google Translate does not recognise Jamaican as a language, we have paradoxically been forced to label the language used in the Jamaican documentary as “English” in order to be able to add the proper Cassidy-JLU subtitles which underline its separate status! We can confidently predict that the YouTube auto-translate function, which we normally commend, is going to struggle with this!

Our aim, in due course, will be to also create a Clilstore transcript incorporating the new Custom Dictionary tool, along similar lines to previous contributions from the Jamaican Language Unit.

We have been demonstrating for some time through “Other Tongues” that the re-purposing in different languages of documentary work in our local community context can be accomplished relatively easily and simply. And we most recently illustrated this at scale with the Children’s Parliament in Barra film. The wider point is that this can be a 2-way street, or perhaps a multi-lane spaghetti junction! With Audrey’s documentary we’ve started with a film made originally in Jamaican and, in a reversal of previous examples, worked up a Gaelic version from it. Not only that, we’ve got Welsh and English versions too!

As hinted in our Duncan Ban MacIntyre piece, “Jamaican in Wales” is just the first of a short series of collections in similar style that explore new fields for Island Voices, including poetic expression, and in “displaced” or “exile” contexts. This is work in progress, with more to come from other island geographies.

Di stuori stil a gwaan. Jos laik Bob Marley se, “Wi faawad in dis jenarieshun chrayomfantli!”

“Baile m’ àraich” – Catrìona Dhuirl

Island Voices re-posts another video from Comann Eachdraidh Sgìre a’ Bhac on the Clilstore platform, as part of the University of the Highlands and Islands CIALL initiative.

“Coinneach visited Catriona MacCarthur (Catriona Dhuirl), who is in her 90s, although she certainly doesn’t look it. She recalls the days of her youth and being brought up in Coll, reminiscing about people and pastimes, community life and some of the effects which WWII had on her generation.”

You can watch the video while reading the wordlinked transcript in this Clilstore unit: https://clilstore.eu/cs/11854

Donnie Macaulay – Sgìre a’ Bhac

March opens with the further extension of our CIALL-supported collaborative work with Comann Eachdraidh Sgìre a’ Bhac through the creation of another wordlinked transcript on the Clilstore platform, this time based on their video of Coinneach MacÌomhair in conversation with Donnie Macaulay. Donnie Macaulay is the son of the late Rev Murdo Macaulay, who was the minister of Back Free Church between 1956 and 1975.

It’s another fascinating recording of naturally spoken Gaelic, full of stories and treasured reminiscences. And now the Clilstore treatment offers enhanced access to Gaelic learners, and any others who may also like to see written Gaelic alongside the spoken word.

Here’s the link: https://clilstore.eu/cs/11851

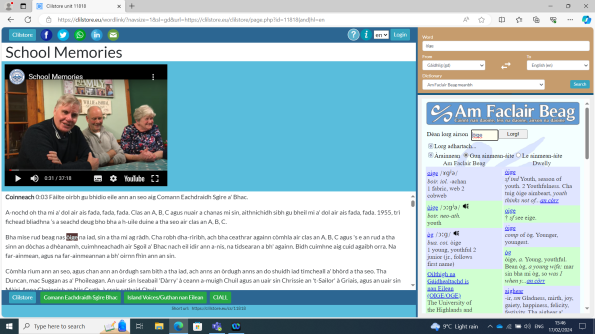

Back School Memories

We’ve previously drawn attention to some of the fascinating YouTube videos coming out of Comann Eachdraidh Sgìre Bhac, and to the fact that a number of the Gaelic ones have now been enhanced with optional same language subtitling (which can also be auto-translated into numerous other languages, including English).

Of course, once the subtitling has been done, that also forms a base on which other platforms can be built – such as a learner-friendly “Clilstore” unit. This is an online tool which creates a new webpage with the video embedded alongside a scrollable text, so you can look at and listen to the video while at the same time following the transcript in real time. Plus, there’s a special trick which allows learners to click on any word they don’t know and immediately gain access to a dictionary translation of it.

So here, with support from the University of the Highlands and Islands’ “CIALL” initiative, is another example of the Clilstore software being put to use with a community-produced recording about School Memories from Sgoil a’ Bhac, with Coinneach MacÌomhair in conversation with some of his former classmates.

Clilstore Unit 11818 – “School Memories”: https://clilstore.eu/cs/11818